December 8, 2002 New York Times

By DANIEL LEWIS

Philip F. Berrigan, the former Roman Catholic priest who led the draft board raids that galvanized opposition to the Vietnam War in the late 1960's, died on Friday in Baltimore after a lifetime of battling "the American Empire," as he called it, over the morality of its military and social policies. He was 79.

His family said the cause was cancer.

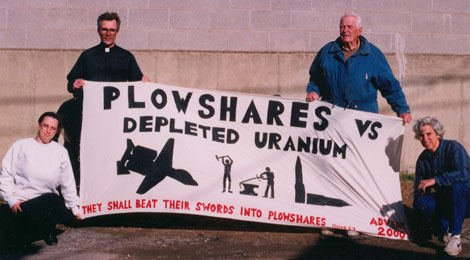

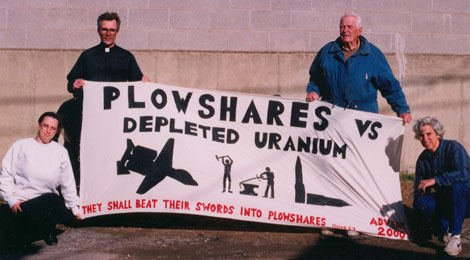

(Above) Phil Berrigan (second from right) protesting depleted uranium

An Army combat veteran sickened by the killing in World War II, Mr. Berrigan

came to be one of the most radical pacifists of

the 20th century - and, for a time in the Vietnam period, a larger-than-life

figure in the convulsive struggle over the country's direction.

In the late 60's he was a Catholic priest serving a poor black parish in Baltimore and seeing nothing that would change his conviction that war, racism and poverty were inseparable strands of a corrupt economic system. His Josephite superiors had previously hustled him out of Newburgh, N.Y., for aggressive civil rights and antiwar activity there; the "fatal blow," he said, had been a talk to a community affairs council in which he asked, "Is it possible for us to be vicious, brutal, immoral and violent at home and be fair, judicious, beneficent and idealistic abroad?"

He hardly missed a beat after his transfer to Baltimore, founding an antiwar

group, Peace Mission, whose operations included picketing the homes of Defense

Secretary Robert S. McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk in December 1966.

By the fall of 1967 Father Berrigan and three friends were ready to try a new

tactic. On Oct. 17, they walked into the Baltimore Customs House, distracted

the draft board clerks and methodically spattered Selective Service records

with a red liquid made partly from their own blood.

Three decades later, Mr. Berrigan remembered feeling "exalted" as the judge sentenced him to six years in prison. From then on, he would be in and out of jail for repeated efforts to interfere with government operations and deface military hardware.

Even before his sentencing for the Customs House raid, Father Berrigan instigated a second invasion, against the local draft board office in Catonsville, Md. Among those persuaded to join was his older brother, the Rev. Daniel J. Berrigan, a Jesuit priest and poet, who had been one of the first prominent clergymen to preach and organize against the war.

The "Catonsville Nine" struck on May 17, 1968, taking hundreds of files relating to potential draftees from the Knights of Columbus building, where the draft board rented space. They piled the documents in the parking lot and set them burning with a mixture of gasoline and soap chips - homemade napalm.

Reporters were given a statement that read, "We destroy these draft records not only because they exploit our young men but also because they represent misplaced power concentrated in the ruling class of America." It continued, "We confront the Catholic Church, other Christian bodies, and the synagogues of America with their silence and cowardice in the face of our country's crimes."

When the police arrived, the trespassers were praying in the parking lot. The cameras loved the Berrigans. In the definitive photograph of the event, seven of the Catonsville Nine are nowhere to be seen. The photo includes only the striking image of two priests in clerical dress, one big and craggy, the other slight and puckish, serenely accepting their imminent incarceration.

The Catonsville raid inspired others in New York City, Milwaukee, Boston, Chicago and other cities, the tactic becoming a sort of calling card of the "ultra-resistance." It also elevated the Berrigan brothers to the status of superstars. "Father Phil" and "Father Dan" were on the cover of Time magazine and illuminated in profiles by the smartest writers.

But many Americans saw them as communists and traitors, or at best naïve dupes of the Vietcong. And among their own allies, grumbling grew about a cult of personality and a certain disdain for anyone unwilling to make the same sacrifices the Berrigans demanded of themselves.

Philip Francis Berrigan was born Oct. 5, 1923, in Two Harbors, Minn., the youngest of six sons of Thomas W. Berrigan and Frida Fromhart Berrigan, a German immigrant. Thomas Berrigan was a frustrated poet and a bullying husband and father. He was also a political radical whose labor organizing activities led to his dismissal as a railroad engineer, after which he moved to Syracuse and bought a poor 10-acre farm.

After high school, Philip was a first baseman in semiprofessional baseball before enrolling in St. Michael's College in Toronto. In January 1943, after one semester, he was drafted into the Army.

The life of black sharecroppers in Georgia, where he had basic training, and the treatment of black soldiers on his troop ship to Europe made an indelible impression on his conscience. So did his own role in infantry and artillery battles that earned him a battlefield commission as second lieutenant. In so many words, he came to consider himself as guilty of murder as the Germans and Japanese. Along with this came the conviction that he had grown up on a diet of nationalistic propaganda in which the good - "white Europeans" - always triumphed over evil - "anyone else."

After graduating from the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass., in 1950, he committed himself to the priesthood and was ordained in St. Joseph's Society of the Sacred Heart in 1955. Later, he earned degrees from Loyola University and Xavier University, both in New Orleans.

The young priest became passionately involved in civil rights and antiwar activities, especially after the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. He was frequently in trouble with his superiors, whom he openly criticized for supporting the status quo, and occasionally with the law. He boasted that he was the first American priest jailed for a political crime.

In the trial that resulted in his second prison term - the trial of the Catonsville Nine in 1968 - the defendants were allowed to talk about their lives and political views but not to argue that some higher morality justified their breaking the law. All were found guilty.

In April 1970, after his appeals were denied, he was scheduled to begin serving a three-and-a-half-year term for the Catonsville incident, to run concurrently with the six-year sentence from the earlier Baltimore raid.

But the Berrigan brothers and two other Catonsville defendants reasoned that if they had been right to break the law in the first place, then it would be wrong to accept the government's punishment for it. So they went underground, and for a time two priests were among the criminals most wanted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Daniel eluded capture until Aug. 11, but Philip was arrested on April 21 in St. Gregory's Church in Manhattan and began serving his sentence in Lewisburg, Pa.

He spent many prison hours praying and filling journals with his trademark polemical writing, which over the years condemned everything from deceptive breakfast cereal advertising (a form of "violence") to the modern church. "The Gospel the church preaches," he wrote, "is a precise statement of the life it leads - a degenerate stew of behavioral psychology, affluent ethics and cultural mythology, seasoned by nationalist politics."

While at Lewisburg, Father Berrigan unwittingly helped set in motion a new controversy.

He had fallen in love with a nun, Elizabeth McAlister of the Religious Order of the Sacred Heart. In a ceremony without witnesses the two had secretly declared themselves husband and wife in 1969. They smuggled love letters past the prison censors through a trusted young inmate, Boyd Douglas, who was allowed outside to attend college classes.

According to the biographers Murray Polner and Jim O'Grady in "Disarmed and Dangerous," Father Berrigan's fellow inmate James R. Hoffa, the Teamsters president, warned that Mr. Douglas was an F.B.I. informant. But this expert opinion was ignored, and the exchanges ultimately became a source of great embarrassment and the basis for fresh prosecution. The letters talked of kidnapping a government official - Henry A. Kissinger was mentioned - and of shutting down government buildings in Washington by turning off the heat or air-conditioning.

The result was a conspiracy trial in 1972 that ended in acquittal on all major charges.

Philip Berrigan was paroled in December 1972. He and Elizabeth McAlister legalized their marriage in 1973. They issued justifications of their union on personal, scriptural and political grounds - and were excommunicated.

From then on the couple lived and worked in Jonah House, a small religiously oriented commune they founded in Baltimore.

Through his antinuclear Plowshares operation, Mr. Berrigan led a series of raids, among them an attack in 1980 at the General Electric plant in King of Prussia, Pa. Two decades later he was still at it, though the world had largely stopped paying attention.

Thus citizen Berrigan, then 77, missed the 2001 premiere of a documentary film about Catonsville. He in an Ohio prison on charges of interference with a weapons system.

In addition to his wife and brother Daniel, Mr. Berrigan is survived by three children, Frida, Jerome and Katherine; and three other brothers, John, James and Jerome.

http://www.nytimes.com/2002/12/08/obituaries/08BERR.html?ex=1040285898&ei=1&en=23cf69380ae91adc